Nike launched the HyperAdapt, its first self-tying shoe, at the beginning of December – some in the press heralded the long-awaited moment as “Back to the Future 2” finally coming to life. And it’s hard not to smile at the thought of magical shoe laces: animating prosaic objects into self-determined, chatty and charming companions has made Disney a fortune (NB: Frozen, Beauty and the Beast). So it’s hard to imagine how Nike could go wrong with this idea, even at the rather ambitious price point of $720 per pair. Surely version 2.0 will be able to chat with you as you prepare to head out for a run, and perhaps even coach you as you exercise.

An article in the Wall Street Journal implied that the point of the new shoes is not really their lacing prowess, it’s that Nike now has something cool to sell you that you can only buy at one of their own retail stores or through their Nike+ app. Not at Dick’s or Foot Locker. That’s a sensible strategy for communicating directly with the consumer, creating urgency to buy now (at full price) and enhancing the brand’s aura of being consistently first to achieve the newest highs in footwear performance (we wrote about how sneaker manufacturers manage to keep their prices so high in a prior post). So the business case is solid, the idea of this is fun, and the shoes are reasonably good-looking.

So why do I feel melancholy and a little bit anxious about this announcement?

At the risk of sounding like a Luddite crank (which I may very well be), I’m just not convinced that all this technological progress in our everyday lives is a good thing for us.

The news is full of wondrous new tech innovations that seem to emerge with ever-increasing frequency: self-driving cars; a robot butler that can make your morning toast; voice-enabled smartphones. Soon you won’t need to know how to drive or even how to boil an egg. Not only will you not need to learn how to write legibly by hand in your native tongue, you won’t even need to learn how to type – just speak and the technology will take it from there.

You won’t need to know how to navigate a supermarket, a department store, or even a website anymore – Alexia, Siri and the gang will be able to do all of your shopping for you via voice command, and you won’t even have to get off the couch. The Internet of Things means that increasingly, you won’t need to understand much about the inner workings of your own house. Buy the right technology, and you won’t have to know how the heater works, or what to do if the pipes burst. Your weekend chore list is getting shorter by the second.

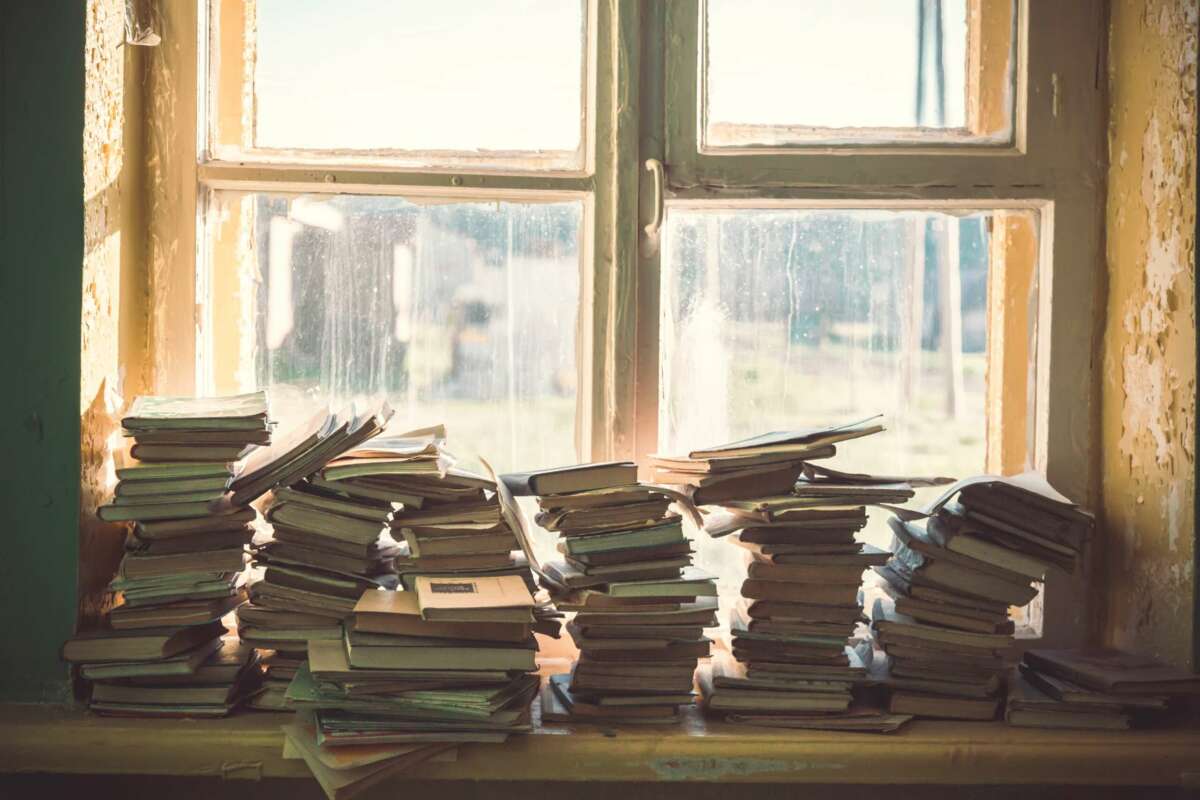

It’s not just practical life skills that you won’t really need anymore. Your level of knowledge about history, pop culture, food, politics, sports statistics and film is also becoming increasingly irrelevant. There was a time when being smart actually meant knowing facts, being able to remember them with no assistance, and being able to draw important conclusions from them. Soon, there’ll be no real need to know anything, because you can just ask Cortana. As long as your digital assistant is at hand, why do you need to have any facts in your head at all?

Once upon a time, people needed a certain level of executive functioning skills just to get through an airport. For example, you needed a boarding pass and you had to keep track of your suitcase. Now, the boarding pass is on your phone and you can buy a smart suitcase that will either text you if you get too far away from it, or even follow you through the airport like a miniature pack mule on wheels. I don’t think the current generation of smart suitcases will fetch you a coffee from the closest Starbucks in the terminal just yet, but that might be the next iteration.

With “follow me” technology and GPS’s everywhere, losing things will soon begin to become impossible. Is this a good thing? Or will the part of our brains responsible for keeping track of things just shrivel and die?

Of course, while almost all of this is new, it’s also the case that almost none of it is.

What was once done by a retinue of butlers and household staff is now being done by technology. That’s all. Things that some human, somewhere in the food chain, once had to master are now increasingly being mastered by machines. Throughout history, the uber-rich and the powerful have always been able to avoid many of the dull quotidian rituals of everyday life that burdened the hoi polloi, because they’ve had an army of helpers to do these things for them.

So isn’t it a good thing that now the luxury of avoiding simple repetitive tasks is available to everyone? That now none of us will lose things; that now all of us can spend our time on higher-order thinking?

I guess so. But here’s the thing: the nadir of a toddler’s life used to be the day she learned to tie her own shoes. In 10 years, that milestone may be as antiquated as teaching a child how to milk a cow. For the past century or so, the best day of a teenager’s life has been the first time he drives a car out of his parent’s driveway alone, to take to the road free, alone and going. In 5 years, will any of us need drivers’ licenses? And what will we do to replace that lost rush?

Every generation grieves for the passing of its norms and rites of passage. I get that. But what will replace the personal satisfaction of mastering a skill, being independent, doing for oneself?

Could this be why the wealthy are embracing adventure travel and exploration with such gusto? Is it why extreme fitness is a growth market? The cliché of the decadent rich is that they have no actual practical skills; that they are soft and physically helpless. I don’t think I’m the only one who feels a primal need to push back against this new wave of technology, which taken to its logical conclusion could render us all slothful and stupid. Why not push yourself to dive deeper under the ocean than anyone has ever gone? Or try to fly to Mars? Or bike across America without stopping? That’s what the uber-rich are doing – and maybe this is why.

Every wave of progress seems to have at some point a bit of a backlash, and some regression back toward the mean. I wonder if this will be true in today’s personal tech arena as well.

Twenty years from now, will the most powerful people be the ones who have technology that does everything for them? Or the ones who have no need of technology at all?