The Luxury Photo Journey is an occasional series here at Dandelion Chandelier. Sometimes we find ourselves in a place so stunningly beautiful that words fail us. In those instances, we’ll let the images do most of the talking.

We were recently in London and decided to make a long-delayed first visit to the soaring Tate Modern museum of international modern and contemporary art on the banks of the Thames in London. Like so many of life’s true luxuries, admission is free, and the building itself is a provocative and stimulating work of art.

The Tate Modern Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

We had only an hour, so we booked an expert tour guide from the luxury British experience company Noteworthy to show us the highlights of the museum. We thought that would give us the lay of the land so that we could return on our own and continue our exploration.

The hot exhibition right now is “Picasso 1932 – Love, Fame, Tragedy,“ the first ever solo Pablo Picasso exhibition at Tate Modern. It features more than 100 paintings, sculptures and drawings, mixed with family photographs and rare glimpses into the artist’s personal life. Three of his extraordinary paintings featuring his lover Marie-Thérèse Walter are shown together for the first time since they were created over a period of just five days in March 1932. Sadly, this one’s not free, unless you’re a member — otherwise the tariff is about $25 per person.

We wanted to explore the complimentary parts of the museum on this first run, so we vowed to return for the Picasso exhibit. Here’s what of we saw on our guided tour of the “best of” what the museum has to offer in its permanent (free) displays.

Gallery at the Tate Modern Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

The Media Networks galleries are an excellent place to start. The works in this section explore the ways in which artists over the past hundred years have responded to the impact of mass media and changes in technology. The exhibition space showcases a diverse range of techniques and materials – from posters and paint to analogue and digital technology – all while raising questions about “feminism, consumerism and the cult of celebrity.”

Here are some of the pieces that stood out for us:

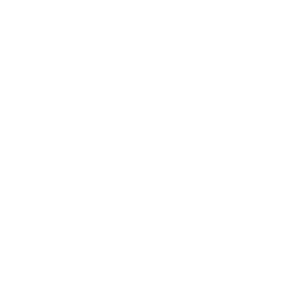

The Advantages Of Being A Woman Artist (1988) is one of a series of posters published in a portfolio entitled Guerrilla Girls Talk Back by the group of anonymous American female artists who call themselves the Guerrilla Girls. Launched in 1984, the group works to expose discrimination in the art world; members protect their identities by wearing gorilla masks in public and by assuming pseudonyms taken from such deceased famous female figures as the writer Gertrude Stein and the artist Frida Kahlo. In the current #MeToo era, this late-1980’s work turns out to be eerily prescient, and highly relevant to ongoing conversations about gender.

The Advantages Of Being A Woman Artist (1988) by the Guerrilla Girls Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Cildo Meireles, the Brazilian conceptual artist, installation artist and sculptor, created Babel in 2001 to express the impact of technology on our ability to communicate effectively with one another. At its base are analog devices, and as the tower grows, the technology becomes more advanced and switches to digital. The soundtrack, which fills the small room that holds the work with a static-filled cacophony, is a statement about modern life in and of itself.

Babel (2001) by Cildo Meireles Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Another don’t-miss section is entitled In the Studio – it includes depictions of artists’ studios as well as abstract works that draw attention to the complex nature of perception. It’s a chance to explore the intimate and intense process of creating art.

Here’s a selection of some of the standout pieces we saw:

Untitled (for Francis) is a 1985 figurative sculpture made from a plaster mold, which is reinforced with fiberglass and sheathed in a skin of dark grey lead, by the British sculptor Antony Gormley. When several of these works were installed in New York City as a summer public art installation, several times a day people called the police to report that a man on a ledge was about to jump. That’s how lifelike and sympathetic these sculptures are.

Untitled (for Francis) (1985) by Antony Gormley Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Pierre Bonnard Coffee (1915) provides a glimpse into the creative process, as the Tate Modern has acquired three sketches of the same work. They demonstrate how the French artist reworked elements of the painting, in particular the placement of the seated woman and the dog. Her position changes markedly from a relaxed intimacy with her pet, to sitting alongside it, to twisting toward it.

Pierre Bonnard Coffee (1915) Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Bridget Riley‘s To a Summer’s Day 2 (1980) – an acrylic painting on canvas comprised of colored waves made of blue, violet, pink and mustard yellow. It’s hard to believe that the canvas is flat and stationary, as looking at this painting immediately gives you a sense of movement, waves, a summer breeze, and lightness. You can almost smell the sand and the sea and feel the sun on your face. Really extraordinary.

To a Summer’s Day 2 (1980) by Bridget Riley Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

The Red on Maroon and Black on Maroon (1959) series were both painted by the American abstract expressionist artist Mark Rothko, best known as a pioneer of color field painting. The movement was characterized by simplified compositions of unbroken color. The works are displayed in a small gallery of their own, and it’s said that if you stare at one of them for about a minute, you’ll start to hear the painting speaking to you – or at least emitting some kind of sound. Of course we tried it. But sadly, we heard nothing. Maybe because we were totally sober? Hard to say.

Red on Maroon (1959) by Mark Rothko Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

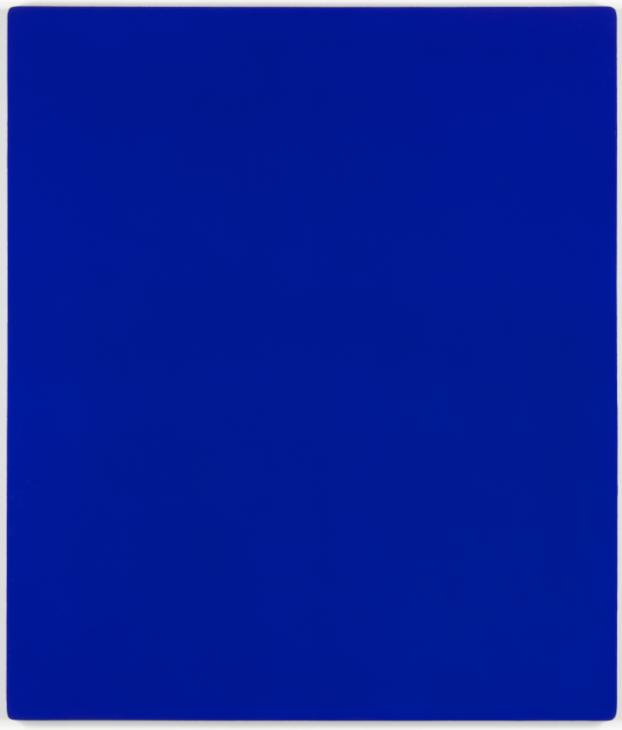

In a similar vein, IKB 79 was one of nearly two hundred blue monochrome paintings Yves Klein made during his short life. He began making monochromes in 1947, considering them to be a way of rejecting the idea of representation in painting and therefore of attaining creative freedom. His vision lives on in fashion with the enduring color Yves Klein Blue.

IKB 79 (1959) by Yves Klein Photo Courtesy of the Tate Modern

We found ourselves drawn to the works of Gerhard Richter, whose series of abstract paintings from 1990 caused our imaginations to engage. His Abstract Painting (726) conveys the suggestion of an original image that has become blurred — the shimmering, romantic, dreamy composition made us think of rain, and wet pavement and old European villages with cobblestone streets. Our tour guide sees a red double-decker bus reflected in a puddle on a rainy street in another of his works, which sounded just right to us.

Abstract Painting (726) (1990) by Gerhard Richter Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

That seems to be a fitting note upon which to end our fast-paced tour of the Tate Modern. The best works of art can literally stop us in our tracks – and make us slow down and really see something that we didn’t even know we needed to see. We left the museum feeling far more connected: to London, to the artists whose works we saw. And to our own inner sense of what’s compelling, beautiful and true. You cannot ask more from an art museum than that. Nicely done, Tate Modern. We’ll be back.