The intimate, deeply civilized and charming Neue Galerie on Fifth Avenue in New York City’s Upper East Side is one of the many hidden gems of Manhattan that too many people miss in their rush toward the neighboring Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Guggenheim. If you haven’t visited yet – or haven’t been there in a while – you owe it to yourself to stop in this spring. The museum is celebrating its 15th anniversary. The current exhibit is deeply moving. And the sacher tortes are as delicious as ever.

The Neue Galerie is a classic house museum: small, gracious, and welcoming, with its permanent artworks having been lovingly collected by one or two owners and therefore quirkier, much more personal and more human than the behemoth collections of the big global players in town. Ronald Lauder presides over this space (his co-founder, Serge Sabarsky, passed away in 1996). The collection is laser-focused on only two things: Austrian and German fine and decorative arts from 1890-1940. With its gorgeous central staircase and its wrought-iron rails; oversized windows with stunning views of Central Park and the parade of pedestrians on Fifth Avenue; and large fireplaces with mahogany and marble mantles, stepping across the threshold is like stepping back in time into Old New York.

We love house museums because they allow us to experience not just the art, but what it was like to live in a certain era – to have presided over a gracious household, to be an acquirer and a steward of an important collection. We always try to visit one in every new city we find ourselves in, in addition to the large cultural institutions – each is a fine complement to the other (on our highly recommended list: Le Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris; Spencer House in London; and the museum in Peggy Guggenheim’s former home, Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, on the Grand Canal in Venice).

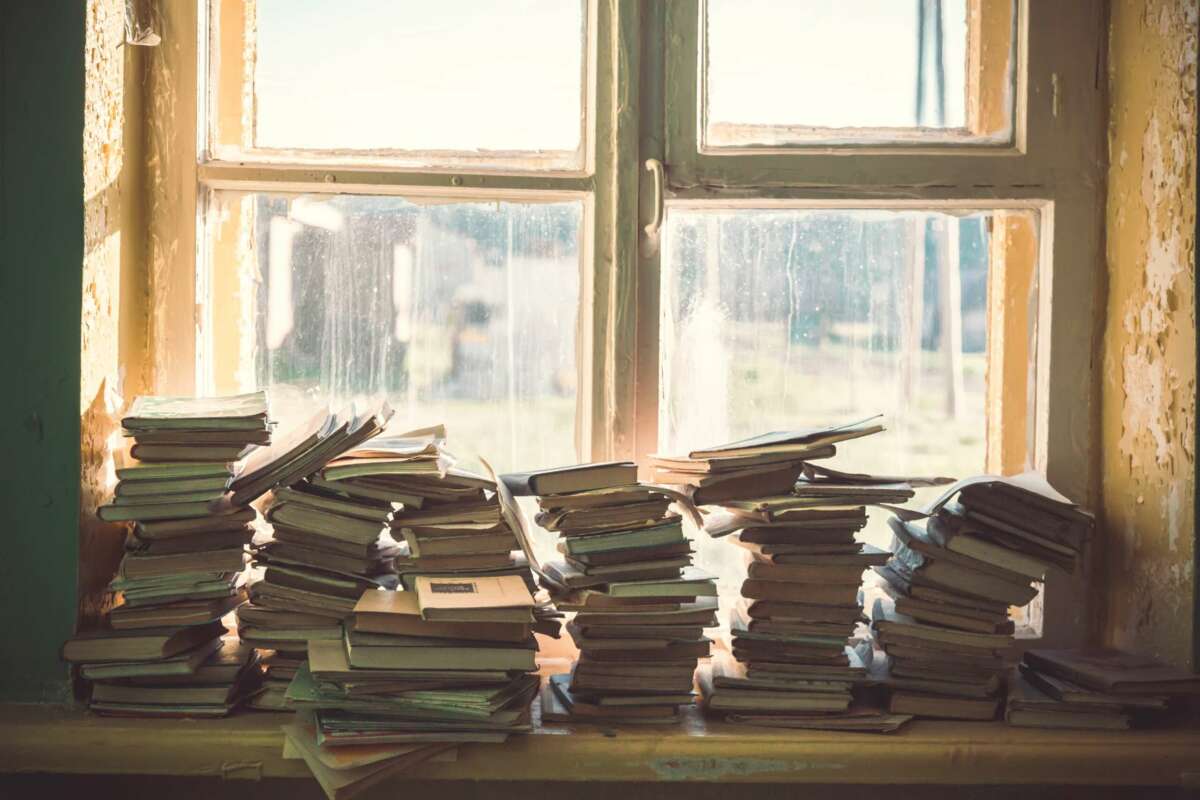

The Dandelion Chandelier Staff Photographer and I recently paid a visit to the Neue Galerie to see the highly-praised Alexei Jawlensky retrospective and to taste a bit of old Vienna at the elegant Café Sabarsky on the first floor of the museum. We have no photos of the artwork to share, as the museum allows no photography in the galleries (although we do have some views of other spaces in the museum in the slideshow below, and we also have a restaurant review for you).

The second floor is home to the permanent collection, which includes the iconic Gustav Klimt 1907 portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (immortalized in the 2015 film “Woman in Gold”), as well as several other paintings, decorative arts and fanciful clocks. The artists represented include Egon Schiele, Josef Hoffman, and furniture-makers Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos. The warm wood paneling, triple-height ceilings and plaster moldings reminded us of how ultra-rich New Yorkers lived during the Gilded Age (and how some still do today).

The third floor is where the temporary exhibitions are staged. We had never heard of Russian-born Expressionist artist Alexei Jawlensky before this visit. This is the first full museum retrospective in the US of his work, organized by curator Vivian Endicott Barnett, who was able to secure 75 paintings created in the period 1900 -1937. At the start of the exhibit we were able to see an extensive timeline of his life and work, and it was quite eventful. Born in 1864, the son of an officer in the Russian Army, Jawlensky was a junior soldier himself when at the age of 18 he visited an art exhibit in Moscow. That experience changed his life: he began to study painting in St. Petersburg, then moved to Munich with a fellow artist. They went on holiday with Vasily Kandinsky, and in Paris were introduced to the work of the Fauves (Cezanne, Gauguin, and Matisse). Jawlensky became a patron of Vincent van Gogh, and a friend of Paul Klee and Franz Marc, making this exhibit a perfect companion to the current Guggenheim Visionaries exhibit. A man ahead of his time, he also studied Buddhism and yoga.

As an artist, he was ambitious and versatile, constructing both striking portraits and gorgeous landscapes. The first gallery contains primarily portraits, many of his wife Helene (who he first painted when she was only 15). Art experts note weaknesses in his brushwork and technique in these works, but to laypeople such as us, what is memorable in paintings like “Dark Blue Turban” is Jawlensky’s ability to brilliantly capture the piercing gaze of his subjects.

Critics view the works in the second gallery more favorably: it displays mostly landscapes and these are among his best-received and enduring works. The landscape colors are deep and luminous, jewel-toned and lush, and reveal the inherent tensions in the transition that the artist and his contemporaries were making over the course of their careers from the representational to the abstract. One in particular, entitled Murnau, depicts a Bavarian village, and seems at once to celebrate the simple bucolic pleasures of the countryside, and warn of the coming storm of World War I (Kandinsky painted a similar landscape called Blue Mountain, currently on display at the Guggenheim).

A third gallery is a study of series – the “variations” that Jawlensky returned to again and again over the course of his career. One motif was an abstract view of a face with its eyes closed and mouth upturned. Alternately called Mystical Heads, Savior’s Faces, and Abstract Heads, there are at least 12 variations on this theme on display, and it’s fascinating to see how slight changes in color and perspective create sharply different images and moods.

The fourth and final room is of paintings the artist created at the end of his life entitled Meditations and Still Lifes. The Nazis banned Jawlensky’s work in 1933, and he subsequently developed severe arthritis and other health issues. Still, he kept painting. In 1934 he began a new series of variations, this time employing a central icon that was perhaps derived from his earlier abstract faces, but that looks quite similar to a cross (he was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church). Each work has colors on either side of the cross, and the disparities between them become more extreme with the passage of time. Religious themes become overt, with many of the works bearing the names of Gospels, prayers, and events transpiring during the liturgical season of Lent. Bach concertos play softly in this gallery, heightening the feeling of elegy and remembrance. It’s a somber and deeply felt mediation on the end of life, filled with color but shaded by strokes of black and a keen awareness of what’s soon to come. Jawlensky died in 1941 at the age of 77. Rather than darkening our mood, though, this final gallery left us feeling gratitude for a life well-lived. What a splendid way to pay tribute to this artist.

Afterward, we settled in at a marble-topped table at the museum’s swanky ground-floor Viennese Café Sabarsky. With only 60 seats, it’s intimate and atmospheric: if you’ve ever visited Austria, or if it’s your native land, this space and its menu will be quite familiar. The period furnishings include a mirrored wall with an extensive and elaborate dessert buffet; dark wood paneling; and a grand piano. The appetizers and entrees include classic Viennese fare: Wiener schnitzel, beef goulash, chicken paprika and spätzle. It’s ideal even if all you’re seeking is an afternoon snack or an early-evening cocktail. There’s a long list of wines and beers, as well as several varieties of Viennese coffee, and the desserts are totally worth saving room for (plum cheesecake, fruit crumble, raspberry poppy seed cake, and chocolate and hazelnut cake, just to name a few).

If you really want to immerse yourself in the milieu of this period, on selected Thursday evenings you can catch the cabarets at Café Sabarsky, which feature live classic European music from 1890-1930.

The Jawlensky exhibit runs until the end of May. Catch it in the whirlwind of everything else you’ve got going on this spring, and you won’t be sorry. And afterward, if you can’t decide between the sacher torte and the apple strudel, by all means, do what we did: have both. As we’ve learned from previous experience, fine art + fine dining = fine time.