Whether you’re a long-time resident or a first-time visitor, the newly-opened Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries at Westminster Abbey are a must-see. Literally. There is no photography allowed in this newly-opened space high above the Abbey (although the press was allowed to take some pics, so you can get a peek at the new space online). If you want to see it in full, you have to go in person. Which you should definitely do. It’s a magical space, and a transforming experience.

The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries opened to the public on June 11th of this year, and we took that as the impetus to visit Westminster Abbey for the first time. To see the new space, you must purchase a ticket to visit the Abbey for £22, plus pay an extra £5 to see the Galleries.

We arrived with a timed entry ticket on a fresh bright summer morning, and found the area surrounding the majestic structure already bustling with traffic, commuters and tourists.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Our ticket first gained us admission to the gated front yard, where we used the time to survey the Abbey’s grand exterior, and to daydream about our fellow visitors in the queue.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

In case you’re wondering (and we were), Westminster is an abbey, which is more like a monastery — as opposed to a cathedral, which is more like a church. The complex contains living and working quarters for the Abbot and other clergy. So while the two words are often used interchangeably, there is a difference.

Onward! The self-guided tour of the nave (the ground floor central part of the building), the choir stalls and the transepts (the area crosswise to the nave) takes about 60 minutes, depending on your pace, making it a perfect addition to our inventory of experiences for Two Hours in London (if you find yourself in London on a business trip or a long layover, we’re sharing suggestions for great ways to get a true taste of the city in two hours or less).

There are no photos allowed in the nave, but if you’d like to see the official images released for personal use, click here.

It’s quite a magnificent space, as you might imagine, and also a bit overwhelming. There are vestrymen and vestrywomen in bright red coats available to answer questions and point out noteworthy features, and it’s well worth chatting with them. They take great pride in their work, and they can share fascinating stories about what you’re seeing.

If we had to choose a “favorite” room, it would probably be The Lady’s Chapel, with its magnificent ceiling — it’s so ornate and delicately carved that it looks like lace.

As we followed the prescribed path through the majestic space, we passed a wall-mounted plaque honoring Cecil Rhodes, and were reminded that at least some of the figures given places of honor here have a lot to answer for.

You’re allowed to take photos once you exit the nave and enter the adjacent Cloisters, with its verdant hushed courtyard.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

The stone corridors of the Cloister are magnificent spaces.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

They’re filled with light and works commemorating some of the leading names in British history, as well as depictions of famous moments in the nation’s past (like the Cook expedition). There are mysterious ancient locks and doors.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

To sit quietly in the Cloisters and reflect on the meaning of the space is a joy. It’s worth it to arrive very early so that you can experience its quiet magic before the crowds arrive mid-morning (after that, it feels a lot more like a crowded hallway than a lovely space to contemplate life).

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

There’s a smaller and quieter courtyard and an expansive garden a short walk away. The walls here are rougher-hewn, and the corridor is watched over by a cherub.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

In the summer, there are often lunchtime musical performances in the garden.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

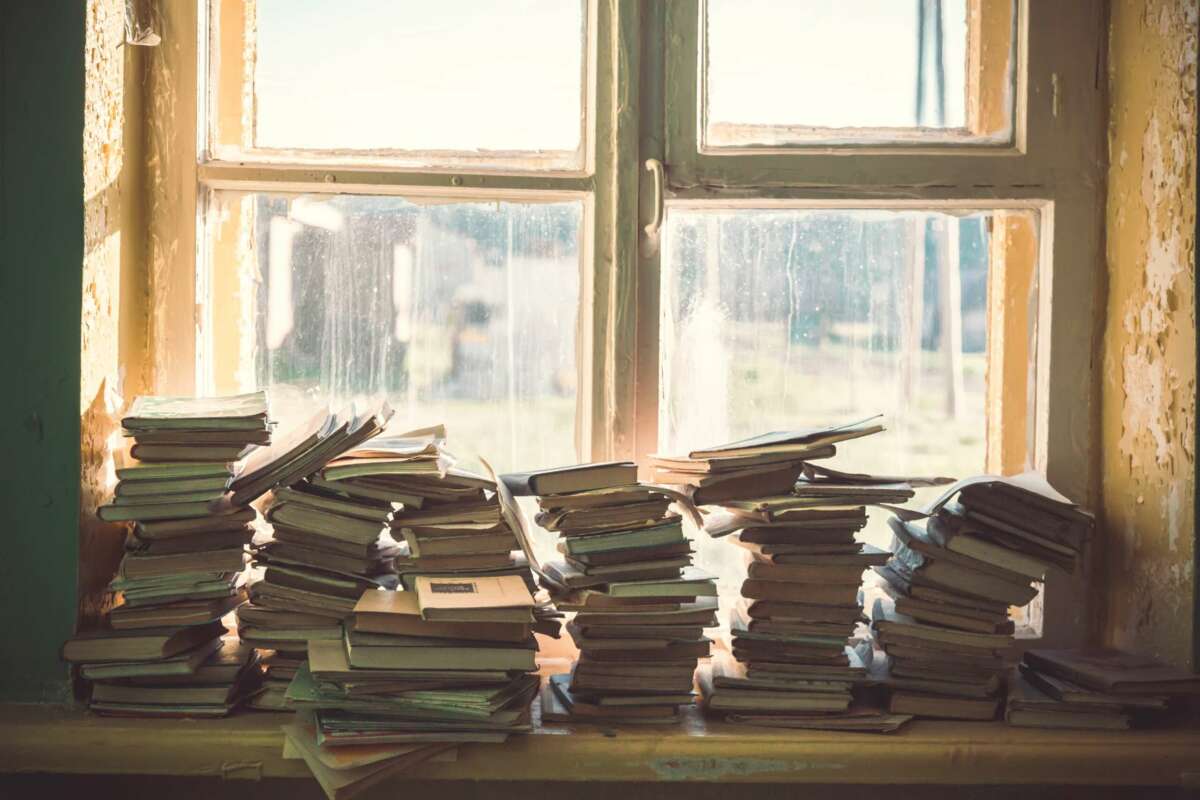

As much as we loved spending time in the various areas of the Abbey, by far our favorite part of the tour of the nave is the famous Poet’s Corner. Anyone who is a writer or an artist – or who dreams of becoming one – will want to linger here.

Many of the great writers, poets and composers of British heritage are buried or commemorated in the Abbey in this designated area. Shakespeare is buried in Avon-on-Hudson, but there’s a large monument to honor him here. Geoffrey Chaucer, Charles Dickens, Jane Austen, C.S. Lewis, Charlotte Brontë, John Donne, George Frederic Handel, Thomas Hardy, George Eliot, T.S. Eliot, Philip Larkin, Oscar Wilde, D.H. Lawrence, Robert Browning, Alfred Tennyson, Rudyard Kipling, Ralph Vaughan Williams and many others are either commemorated or actually interred here.

Just looking at the names reminds you of how many brilliant artists came from England. There’s a collective energy that seems to emanate from this space that will make you want to return to your desk, or your studio, and set to work trying to create something brilliant. There’s a really good vibe here.

It’s the Poet’s Corner that happens to be the waiting area for the magical Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries, located high above the Abbey in a 13th-century triforium (according to the Webster-Merriam dictionary, a triforium is “a gallery or arcade above the arches of the nave, choir, and transepts of a church.”) It was used for storage for most of its life, so in plain English, you can think of this space as the attic of the Abbey.

It cost almost £23 million to renovate the triforium. The enhancements included the construction of Weston Tower, a slender structure made of lead and stone that hugs the walls of the Abbey.

One of the first things you see upon entering the tower’s ground floor is a series of floor tiles with the names of prominent donors – among them Goldman Sachs (we guess this is proof positive that their former CEO really was doing the Lord’s work). The stained-glass windows that encase the stairway also feature the names of various patrons of the renovation.

The Galleries are 52 feet above the floor of the Abbey, which means that a visit requires an ascent. There are two options for doing so: a lift or a narrow staircase with 108 stairs.

If you’re able, definitely take the stairs. They twist so much that they’re practically circular, and they’re surrounded by glass walls that showcase incredible views. As you climb, you can see the stonework, flying buttresses and stained glass windows of the Abbey at close range – all architectural elements that were impossible for the public to see up close until now.

Weston Tower Staircase

Once you arrive, you’ll find yourself in a space filled with light, with thick exposed arched and jointed wooden roof beams, a low timber ceiling, and magnificent stained-glass windows. The lighting is dim, and the sound level is hushed. It feels like a secret space, filled with wonders. And no one is taking selfies! So everyone there is actually engaged in what’s on view.

The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries

As we explored, these Galleries reminded us a bit of the Smithsonian Museum; it has that same delightful feel of a nation’s attic, stuffed with marvelous historical treasures.

Near the entrance, our eyes lit on a series of small white sculptures on rough wooden plinths. We were delighted to find that one of them was Dr. Martin Luther King Junior! A woman next to us said “Yay! There’s a woman here!” It was Catherine of Russia, the country’s longest-ruling female leader. Dietrich Bonhoeffer, German pastor, theologian and anti-Nazi dissident, was also among them.

The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries

We can’t overstate how deeply we were moved to find an African-American hero in a place of honor in this space. It totally erased any lingering bad feeling we had about that wall plaque of Cecil Rhodes, and instead make us feel a ray of hope. The newest galleries – the ones that perhaps matter the most as a statement about the character and values of a nation – are inclusive, celebrate a diverse array of leaders, and feel both ancient and modern. You can’t ask for more than that.

There are so many treats and never-before-seen treasures in the Diamond Jubilee Galleries that it’s hard to say which was best. For example, the royal marriage licence for HRH Prince William and Miss Catherine Middleton is on display for the first time here. England’s oldest surviving altarpiece, thought to have been the centerpiece of Henry III’s Abbey, is here. So is the 14th century Liber Regalis, a guide to staging coronations and royal funerals at the Abbey that still forms the basis of royal ceremonies today. There is a Queen’s coronation chair, used for the crowning of Mary II in the late seventeenth century.

The true thrill, though, is that at this height, you’re able to actually understand the architecture and floor plan of the nave. As you peer over the triforium edge, areas that are hard to appreciate and fully comprehend at floor level start to make sense. This is a wonderful way to fully experience the glories of the Abbey. It’s also a special place for prayer and quiet reflection if you’re so inclined – the timed entries mean that the Galleries aren’t crowded and you have the luxury of time and personal space.

The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Galleries

We descended from this hallowed aerie with a sense of peace and connection that we hadn’t expected.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Back on the ground, we saw the Abbey with new eyes, and with a great deal of reverence.

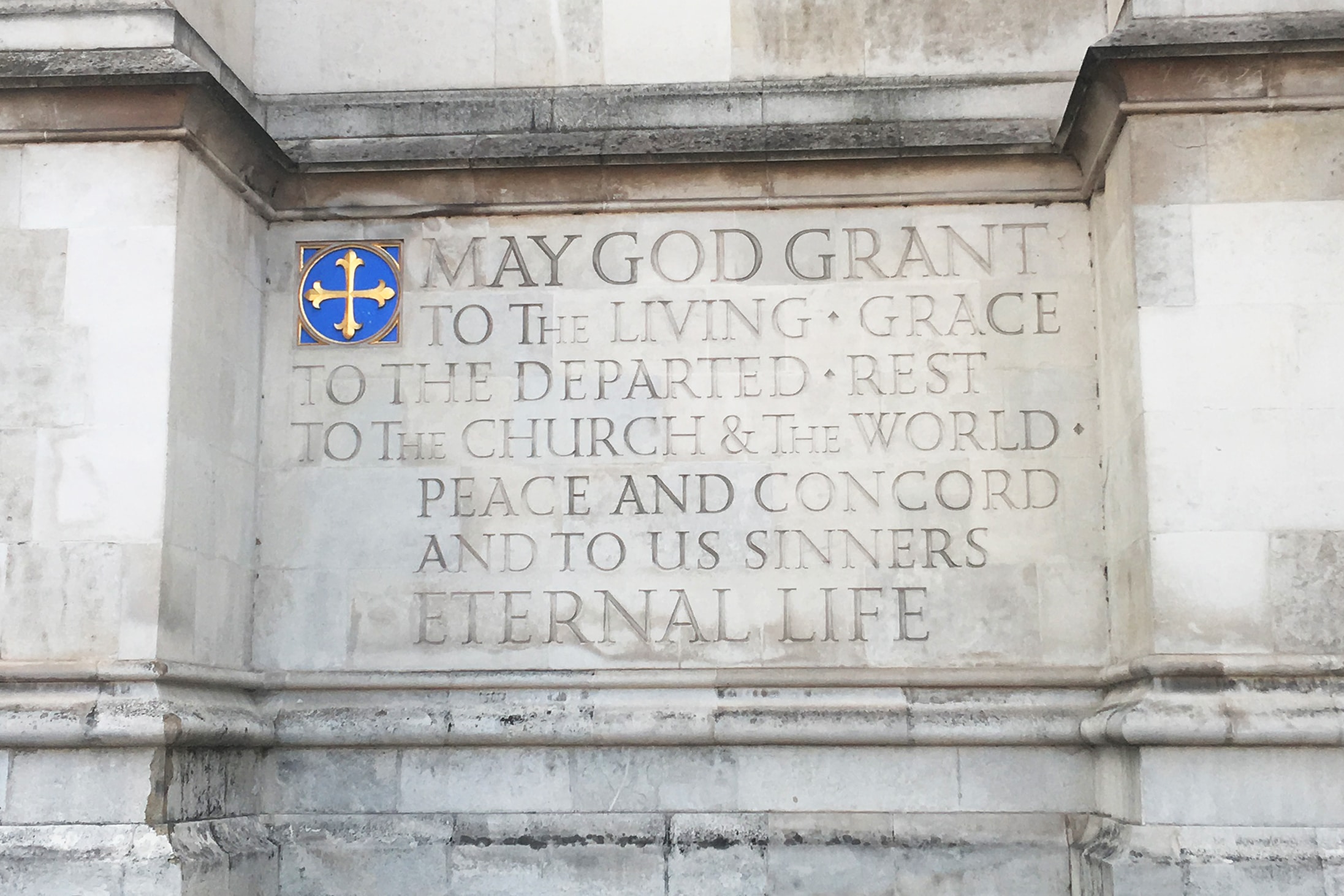

At some point while you’re visiting, you’re highly likely to hear one of the prayers that is shared over the public address system once an hour. It’s a prayer for peace among all nations and cultures of the world, and for just one moment as you breathe in the air of this hallowed space, it feels as if that hope might actually become real.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier

That this is a space that welcomes and shelters all who choose to enter. In times like these, that’s a true luxury to be treasured.