When we go to a museum, what are we hoping to experience? Awe? Escape? A jolt of energy? Or perhaps a sense of deeper understanding. A feeling of connection with the past. Maybe even a glimpse of the future. At a recent visit to the Met, we made a spontaneous detour to see an exhibit that we normally would have passed by. And we felt all of these things. If you can, you should definitely see this one for yourself (and if not, we’re sharing photos): there’s epic beauty and human struggle on display at the vital Winslow Homer Crosscurrents exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum (aka the Met) in New York City.

Epic Beauty and Human Struggle at Winslow Homer Crosscurrents at the Met

Sometimes the best museum exhibit is the one you stumble across, rather than the one you made a mental appointment to see.

That was the case for us on a recent visit to the Met. We went to see the fashion exhibit (more on that in a future post). But while we were there, we wandered around a bit and came across Crosscurrents, an exhibit of the watercolor and oil paintings of Winslow Homer.

Photos of Winslow Homer Crosscurrents exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum (the Met) in New York City. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Now, we don’t know about you, but hearing that name left us feeling a bit . . . meh. Another old American dude painting epic landscapes about men fighting each other, or wild animals, or the elements, or . . . whatever. Hard pass, thanks.

Dear reader, we were wrong.

the magic only a great museum exhibit can generate: a deep emotional connection to art that we didn’t think was “for us.” And appreciation for the complexities inherent in great artists and great art.

[white_box]Join our community

For access to insider ideas and information on the world of luxury, sign up for our Dandelion Chandelier newsletter. And see luxury in a new light.

sign up now >

[/white_box]

Here are some of the images we saw and facts that we learned from this unexpected walk through the American past. Specifically, the post Civil War era, when the narrative of heroes and villains, victims and perpetrators, and the moral high ground itself were all in active dispute long after the fighting stopped. Making one artist’s vision even more influential and important than in calmer moments in American life.

highlights of Winslow Homer Crosscurrents at the Met museum

a Reconstruction era view

The exhibit begins with what the curator notes is “a rare image in Homer’s art of Black and White children together, Weaning the Calf.” In it, a young Black boy wrestles in tattered work clothes with an unruly animal while two neatly dressed White boys watch passively. It’s a preview of the artist’s ongoing preoccupation with humans in conflict with nature. But it’s also a highly unusual rendering of an industrious Black figure exercising agency and control that speaks to the promise of Reconstruction.

Photos of Winslow Homer Crosscurrents exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum (the Met) in New York City. Weaning the Calf, 1885. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Wind, waves and water

Seascapes and the struggle of humans with natural forces – especially storms, waves and water – were a core theme that Homer returned to repeatedly throughout his career. The Met cleverly stages this exhibit as a series of frames, through which one can see what’s coming – and also what’s past. The azure blue of the sea is everywhere – sometimes signaling calm. Sometimes serving as a place of work. And in the most epic images, serving as a metaphor for all of the natural world.

Photos of Winslow Homer Crosscurrents exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum (the Met) in New York City. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

There’s an entire section devoted to Homer’s early works depicting humans struggling with the sea. There are images of rescues; of lone seafarers fighting the waves. One particularly poignant one shows a woman holding an infant at the shoreline as ominous waves crash against the sand. The curator’s notes explain that this work was a homage to the women of a New England town who helped avert disaster when flooding threatened to obliterate their homes.

Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Caribbean fishermen

Images of Black men begin to appear in Homer’s work during this period, and the exhibit details how this focus deepened when Homer began spending time in the Caribbean. Homer describes the Bahamas as “the best place I’ve found,” and he also spent long months in Cuba, Florida and Bermuda (where it is said Shakespeare’s The Tempest was set).

The artist was unusually attuned to the social stratification and the imperial presence of the British in the Caribbean, even as he was enamored of the region’s natural beauty. The curator notes that Homer was struck by “the daily lives and labors of the islands’ Black inhabitants,” depicting them in watercolors that vibrantly captured the turquoise sea, the tropical light and the dramatic skies overhead.

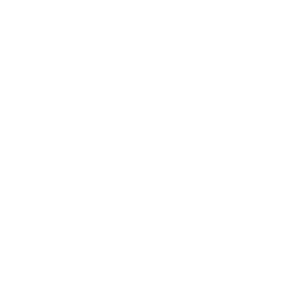

For instance, the watercolor Shark Fishing, 1885, depicts two Bahamian fishermen working to reel in a large shark. The image proved to foreshadow Homer’s epic work, Gulf Coast, as did many other depictions of fishermen and sailors pitched in conflict with sharks, sea creatures and tempests.

Winslow Homer, Shark Fishing, 1885. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

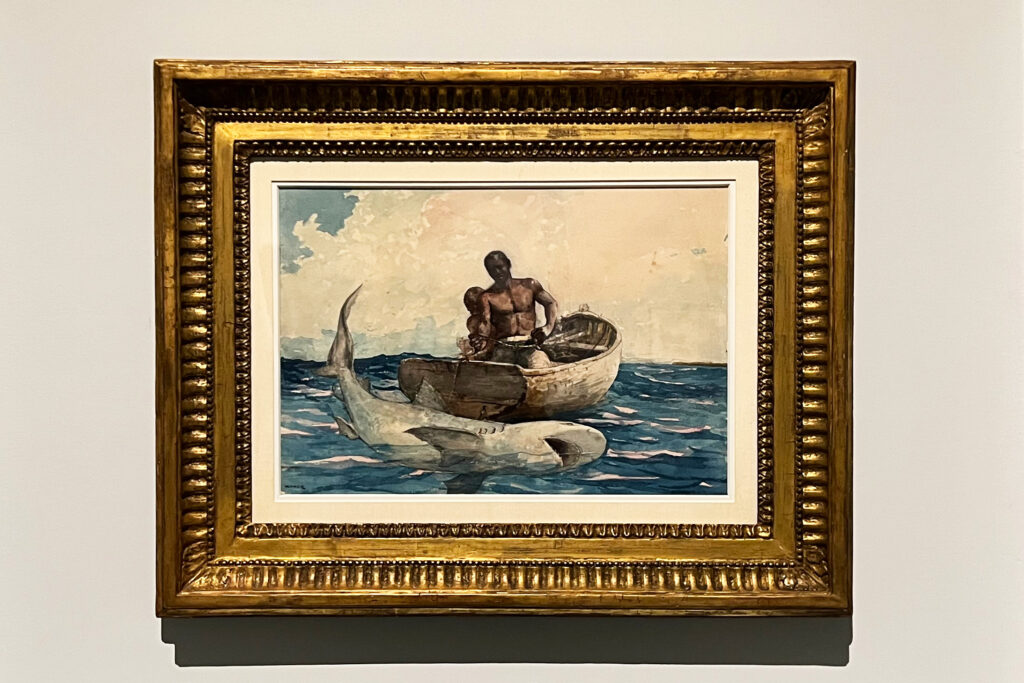

Much later in his life, Homer returned to this subject. The Bather, 1899, is an example of his work from his second visit to the Bahamas in 1898-99.

Winslow Homer, The Bather, at the Met Museum.

At 62, he seemed “to have reveled in depicting the bodies of vigorous Black men.” The curator notes that “inherent in the images is a tension related to racial politics and class disparities, as the older White artist recorded the robust young Black men.”

In the watercolor Nassau, 1899, he depicts Bahamian men working at sea and “included discarded cannons – artifacts from one of the island’s British forts – splayed across the beach.”

Winslow Homer, Nassau, at the Met Museum in New York. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Race and society

That very tension – of a visitor from the majority culture depicting the everyday lives of the indigenous people in a foreign land – is present in many of the canvases on display. And it had been part of Homer’s work for some time.

For example, in A Garden in Nassau, 1885, Homer painted a watercolor of a small child at the edge of a palatial estate sheltered by an enormous palm tree. On first blush, the image appears to be an advertisement for a tropical paradise. Which in fact, it was.

Winslow Homer, A Garden in Nassau, 1885, at the Met Museum in New York. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

The Bahamian government sought to attract American tourists after the Civil War and this was one means of luring them to vacation there. But the image also plainly notes “the exclusion of Black islanders from aspects of Bahamian society. The coral and limestone wall . . . separates the child from the landscape beyond.”

Of course, not every work had a social message embedded in it. Many of the watercolors of tropical enclaves are simply beautiful renderings of nature and luxury homes. For instance, in Bermuda, Homer won great acclaim for Flower Garden and Bungalow, Bermuda, 1899.

Winslow Homer, Flower Garden and Bungalow, Bermuda,1899. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Flowers, palms, sun and sky – he exhibited this picture-postcard work at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo and the Met purchased it after his death in 1910.

the gulf stream, 1899

All of these experiences and locales – at least in the view of this exhibit at the Met – led inevitably to Homer’s masterpiece, The Gulf Stream, 1899. The curator notes that it’s “an epic scene of conflict between humankind and nature,” and “one of his most complicated and consequential works.”

Some saw it as a reflection of Homer’s sense of loss and isolation after the death of his father. Others as “a more universal rumination on mortality.” It was the only Caribbean seascape the artist painted in oil, not watercolor. And he chose to depict a Black figure, which cannot have been a minor consideration. It’s impossible to view the work now – and surely then – without thinking about race, power and agency.

Winslow Homer, The Gulf Stream, 1899, at the Crosscurrents exhibit at the Met Museum. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

The Black man is surrounded by immediate threats to his life: sharks, a waterspout, the imminent collapse of his small boat. The mast has broken off, and there is neither a sail nor a rudder. His shirt and shoes are gone. Who could summon the will to have agency after so much loss?

A closer look reveals that stalks of sugarcane are tossed across the deck of the vessel – evoking transatlantic commerce, including the slave trade. What has brought him to this place? Work, the need to earn a living under dangerous conditions? He is not dressed for a leisurely sail. His expression is resolute, despite being in mortal danger. Where the artist might have depicted stark terror or helplessness or resignation, there is instead a sense of fortitude and endurance.

[white_box]Related Post

Poignant patriotism on view at the Whitney Biennial 2022

read more >

[/white_box]

Very few Black people would find a situation in which they are alone and surrounded by peril from all sides unfamiliar. That is often a common condition of being Black in America. What’s unusual and extraordinary is that a White person chose to portray such a moment at such a grand, timeless and heroic scale.

That was the moment of revelation and awe for us – the idea that this lonely sense of being engaged in an unfair and probably unwinnable fight, during which one has to maintain a demeanor of stoicism and grace, could have been captured so perfectly by someone who seemingly would have no reason to feel that way himself.

We paused then – and have paused a few times since – to hold onto that feeling. It’s a gift that echoes through over a century: in the depths of our struggle, we are seen. Our feelings are not insignificant – they are important. And universal. And perhaps we are not so very alone after all.

woodland life

Near the end of the exhibit we see a number of works from Homer that ostensibly at least have nothing to do with the sea. Or with the eternal struggle between humans and nature. Here, animals themselves are the protagonists.

Photos of Winslow Homer Crosscurrents exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum (the Met) in New York City. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

fox hunt, 1893

For example, in Fox Hunt, 1983, Homer won praise for his ability to channel the scene from the perspective of the fox. “Homer has removed any trace of human prescience and focused on the Darwinian struggle of natural selection in the animal kingdom . . . an ominous flock of hungry crows become predators” and the fox is their prey. It’s a haunting scene of vulnerability and threat.

Winslow Homer, Fox Hunt, 1893, at the Met Museum in New York.

right and left, 1909

Similarly, in Right and Left, 1909, we see two water fowl midair. One duck wears a terrified expression. The other is upside down and plummeting to earth.

Winslow Homer, Right or Left, 1909, at the Met Museum in New York.

A miniscule image of a hunter, a puff of smoke and a short flash of light tell a story of life and death that may be as random as whether one is on the right. Or on the left.

Photos of Winslow Homer Crosscurrents exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum (the Met) in New York City. Photo Credit: Dandelion Chandelier.

Winslow Homer at the Met is an eye-opening must-see exhibit

So much to take in, and so much of life in such a brief walk through a museum exhibit. What more can we ask from our cultural institutions than that?

If you decide to see Crosscurrents – and you should – you have until July 31, 2022. And if you miss it, you can get the exhibit catalog here. We hope it moves you, dear reader.

join our community

For access to insider ideas and information on the world of luxury, sign up for our Dandelion Chandelier Newsletter here. And see luxury in a new light.

Pamela Thomas-Graham is the Founder & CEO of Dandelion Chandelier. A Detroit native, she has 3 Harvard degrees and has written 3 mystery novels published by Simon & Schuster. After serving as a senior corporate executive, CEO of CNBC and partner at McKinsey, she now serves on the boards of several tech companies. She loves fashion, Paris, New York, books, contemporary art, running, skiing, coffee, Corgis and violets.